CM-Notes

Notation#

$ F_i(\{q\}) $ is the force on ith particle. $ \{q\} $ is the set of cordinates of all particles.

If there are N particles in the system,

Configration space: 3N dimensional space, records positions.

State space: 6N dimensional space, records position and velocity.

Phase space: 6N dimesnional space, records position and momentum.

Newton’s second law#

gives us 6N equations.

$$ \begin{align*} \dot{p}_i &= F_i(\{q\}) \\ \dot{q}_i &= \frac{p_i}{m_i} \end{align*} $$

Thus, if forces are known, we can compute trajectory in 6N dimensional configration space.

if we denote $ p = \sum_{i=1}^{i=N} p_i $,

Newton’s third law,#

every force has equal and opposite reaction

can be used to derive conservation of momentum.

$\dot{p} = 0$.

What this tells us is if we start our trajectory at some 6N-D point in configration space, all the points in the trajectory have the same momentum. In some sense, system evolves on a contour of constant momentum.

Energy#

Potential Energy Principle: All forces derive from a potential energy function $V(\{q\})$.

For particle moving in 1 dimension,

$ F(q) = -\frac{dV(q)}{dq}$.

Potential energy can be computed as $V(q) = - \int_{-\infty}^q F(q’) dq’$.

Potential energy is not conserved. Sum of potential energy and kinetic energy are conserved.

Kinetic energy: $T = \frac{1}{2} mv^2$.

More than one particles, three dimensions. If the system has N particles, the i in $q_i$ can index any of the 3N elements of the configration space.

Principle: For any system there exists a potential function $V(\{q\})$, such that,

$$ F_i(\{q\}) = - \frac{\partial V(\{q\})}{\partial q_i} $$

In general mathematics such function need not exist for a collection of $F_i$s. This law represents conservation of energy.

Lagrangian#

For one particle in one dimension#

We are given $q(t_0)$ and $q(t_1)$.

$L(q, \dot{q}) = T - V = \frac{1}{2}m\dot{q}^2 - V(\{q\})$

Action $A = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} L dt$.

Principle of least action tells that the particle chooses a trajectory (the function q) which minimizes the the action.

Principle of least action gives Euler-Lagrange equations.

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}} - \frac{\partial L}{\partial {q}} = 0 $$

For multidimensional motion of many particles#

Euler-Lagrange equations are given by,

$L(\{q\}, \{\dot{q}\}) = \sum_i \frac{1}{2}m_i\dot{q}_i^2 - V(\{q\})$.

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_i} - \frac{\partial L}{\partial {q_i}} = 0 $$

Lagrangian packs all the equations of the motions concisely.

$\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_i}$ is called generalized momentum conjugate to $q_i$. This can be motiviated by thinking of $q_i$ as cartesian coordinates and $L = \frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2$. Depending upon the Lagrangian, conjugate momentum may not have familiar form, but it is always difined by the formula $p_i =\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_i}$.

So, if the Lagrangian does not depend on $q_i$, $\dot{p}_i = 0$, i.e. the conjugate momentum is conserved. Such coordinates are called cyclic coordinates.

Another example of cylic coordinates#

$ L = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{x}_1^2 + \dot{x}_2^2 ) + V(x_1 - x_2)$. It does look like that L is a function of $x_1$ and $x_2$, so neither of these is cyclic coordinate. But, if we do change of variables, $$ \begin{align*} x_+ &= \frac{x_1+x_2}{2} \\ x_- &= \frac{x_1-x_2}{2} \end{align*} $$

the Lagrangian can be rewritten as, $L = m(\dot{x}_+^2 + \dot{x}_-^2 ) + V(2x_-)$. Now the momentum conjugate to $x_+$ is conserved. $p_+ = 2m\dot{x}_+ = m(\dot{x}_1 + \dot{x}_2)$, so the total momentum is conserved.

If $ L = \frac{m}{2}(\dot{q_1}^2 + \dot{q_2}^2 ) + V(a q_1 - b q_2)$, then

$$ \begin{align*} \dot{p}_1 &= -a V(a q_1 - b q_2) \\ \dot{p}_2 &= b V(a q_1 - b q_2) \\ \end{align*} \text{.} $$

Law of conservation of momentum has changed. Instead of conserving $p_1 + p_2$, $bp_1+ap_2$ is conserved. If V was a non linear function of $q_1, q_2$, there wouldn’t be law of conservation.

Symmetries#

$q_i’ = q_i’(q_i)$. We are moving the whole system to the new location. This change changes the system. For example, potential energy(so the Lagrangian) may change.

Symmetry is the coordinate transformation that does not change the value of the Lagrangian.

Examples#

$L = \frac{1}{2} \dot{q}^2$. And the transformation $ q \rightarrow q + \delta$. Here the $\dot{q}$ does not change, so L also doesn’t change.

If the Lagrangian had a potential ($V(q)$) term in it, unless the potential is a constant independent of q, change in q changes the potential. In that case there is no symmetry.

Example Sym.1#

If, potential was a function $V(q_1 - q_2)$, then under the transformation $$ \begin{align*} q_1 &\rightarrow q_1 + \delta \\ q_2 &\rightarrow q_2 + \delta \end{align*} $$ L is symmetric.

Example Sym.2#

If, potential was a function $V(aq_1 + bq_2)$, then under the transformation $$ \begin{align*} q_1 &\rightarrow q_1 + b\delta \\ q_2 &\rightarrow q_2 - a\delta \end{align*} $$ L is symmetric.

Example Sym.3#

If, $ L = \frac{1}{2} (\dot{x}^2 + \dot{y}^2) + V(x^2 + y^2)$, then there is rotational symmetry. That is, rotating the point around origin by angle $\theta$ does not change the lagrangian.

$$ \begin{align*} x &\rightarrow x cos\theta + y sin\theta \\ y &\rightarrow -x sin\theta + y cos\theta \end{align*} $$

For small angle $\delta$, $sin\delta = \delta$ and $cos\delta = 1$. $$ \begin{align*} x &\rightarrow x + y \delta \\ y \rightarrow -x \delta + y &= y - x\delta \end{align*} $$ Plugging this into the lagrangian, we can see that (in the first order of $\delta$) lagrangian does not change.

General notion of symmetry#

In general, the shift is parameterized by infinitesimal $\delta$ and is given by $\delta q_i = f_i(q) \delta$.

| example | $f_1$ | $f_2$ |

|---|---|---|

| Sym.1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sym.2 | b | -a |

| Sym.3 | y | -x |

Change in velocity then is given by $\delta \dot{q_i} = \frac{d}{dt} \delta q_i$.

A continuous symmetry is an infinitesimal transformation of the coordinates for which the change in the Lagrangian is zero.

If we assume that system evolves along a trajectory that satisfies Euler-Lagrangian equations, we can prove that symmetry implies $\cal{Q}$ is conserved. Where $\cal{Q} = \sum_i p_i f_i(q)$.

Applying this to Sym.3, we see that $l = p_x y - p_y x$, aka angular momentum, is conserved.

Time translation invariance#

A system is time-translation invariant if there is no explicit time dependence in its Lagrangian.

e.g. harmonic motion due to spring $L(x, \dot{x}) = \frac{1}{2} (m \dot{x}^2 - k x^2)$. Here neither the mass m, nor the spring constant k depend on the time.

If spring constant changes with time i.e. k(t), there would be no time translation invariance.

Now if $L = L(q_i, \dot{q}_i, t)$,

$$ \frac{dL}{dt} = \sum_i \left( \frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{q_i}} \dot{q}_i + \frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{\dot{q}_i}} \ddot{q}_i \right) + \frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{t}} $$

Using Euler-Lagrangian equations, we can simplify above to

$$ \frac{dL}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt} \sum_i p_i \dot{q}_i + \frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{t}} \text{.} $$

If we define $H = \sum_i p_i \dot{q}_i - L$, we see that $$\frac{dH}{dt} = -\frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{t}} \text{.}$$

Conclusion: H changes only if L has explicit time dependence. In other words, if the system is time-translaction invariant then quantity H is conserved.

H is called Hamiltonian, and is an energy of the system.

Example: Motion of a particle in a potential#

$$ \begin{align*} L &= \frac{1}{2}m \dot{x}^2 - V(x) \\ p &= \frac{\partial{L}}{\partial{\dot{x}}} = m \dot{x} \\ H &= p \dot{x} - L \\ &= m \dot{x}^2 - \frac{1}{2}m \dot{x}^2 + V(x) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}m \dot{x}^2 + V(x) \\ \end{align*} $$

There are systems for which the Lagrangian has a more intricate form than just T - V. For some of those cases, it is not possible to identify a clear separation into kinetic and potential energy.

General Definition of Energy: Energy equals Hamiltonian.

In Lagrangian formulation, the focus is on the trajectory in the configuration space. here, the equations are second order. So knowing just the $q_i$s is not enough. We also need initial velocities.

In Hamiltonian formulation, the focus in on the trajectory in the phase space.

The first step in the Hamiltonian formulation is to replace $\dot{q}$’s with $p$’s. This is easy to do in normal cartesian coordinates.

in the particle on a line, $ H = \frac{1}{2} m \dot{x}^2 + V(x)$. Replacing $\dot{x} = \frac{p}{m}$, we get, $ H = \frac{p^2}{2m} + V(x)$.

$$ \frac{\partial H}{\partial x} = -\frac{dV}{dx} $$

Using $f = ma$ we can rewrite the above equations as $$ \dot{p} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial x} $$

Thus we have two equations,

$$ \begin{align*} -\frac{\partial H}{\partial x} &= \dot{p} \\ \frac{\partial H}{\partial p} = \frac{p}{m} &= \dot{x} \end{align*} $$

General system#

$$ \begin{align*} H &= H(q_i, p_i) \\ \dot{p_i} &= -\frac{\partial H}{\partial q_i} \\ \dot{q_i} &= \frac{\partial H}{\partial p} \end{align*} $$

So we see that for each direction in phase space, there is a single first-order equation. If we know initial $p, q$, using above equations we can predict the future.

Harmonic Oscillator#

$$ L = \frac{m \dot{x}^2}{2} - \frac{kx^2}{2} $$

With the change of variable $q = (km)^{\frac{1}{4}}$,

$$ L = \frac{\dot{q}^2}{2\omega} - \frac{\omega q^2}{2} $$

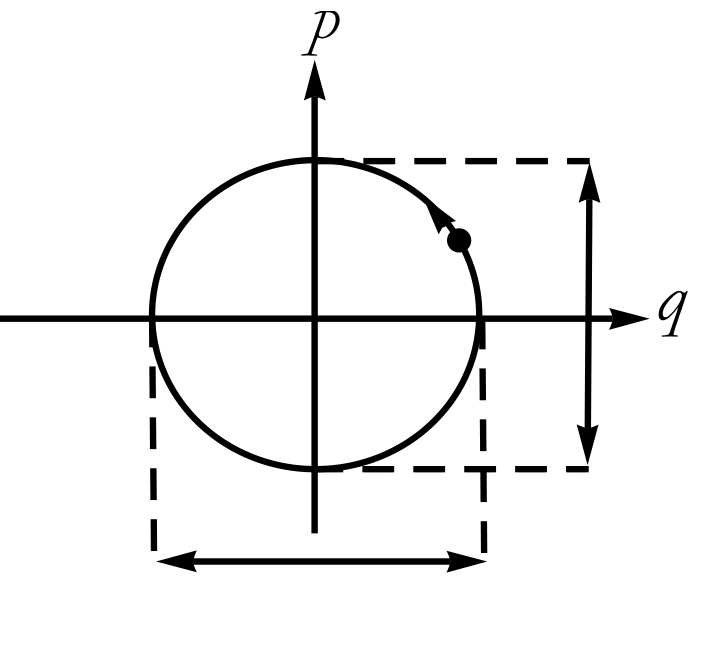

The conjugate momentum $p = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}} = \frac{\dot{q}}{\omega}$. This gives us $H = \frac{\omega}{2} (p^2 + q^2)$. (Exercise. Recall: $H = \sum_i p_i \dot{q}_i - L$.)

From that,

$$ \begin{align} \dot{p} &= -\omega q \\ \dot{q} &= \omega p \end{align} $$

Thus Hamiltonian formulation gives us two first order equations.

Solving Euler-Lagrangian equation, on the other hand gives us single second order equation. $\ddot{q} = \omega \dot{p}$. These two are equivalent, and can be seen by substituting the first equation in the time derivative of the second equation of the Hamiltonian.

Notice that because of constant energy, in the phase space the particle moves along a circle of fixed radius.

Phase Space Fluid#

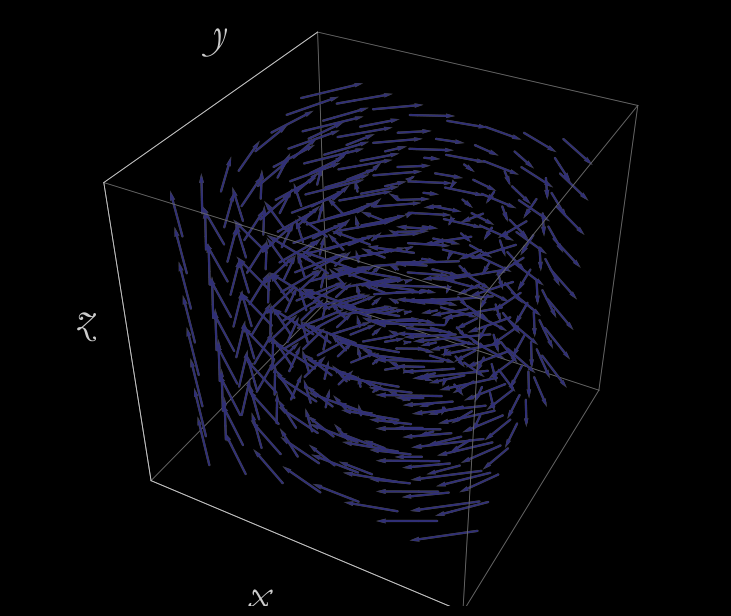

One can imagine a trajectory starting with arbitrary point (p, q) in the phase following the hamiltonian equations.

$$ \begin{align*} \dot{p_i} &= -\frac{\partial H}{\partial q_i} \\ \dot{q_i} &= \frac{\partial H}{\partial p} \end{align*} $$

We can imagine the phase space made of infinite points. This can be seen as a fluid in a phase space. The fluid moves using hamiltonian equations.

This flow has certain features.

- If a point starts at given energy H(q, p), it remains with the same value of energy. The surfaces of the energy are defined by $H(q, p) = E$. For each value of E, we have a surface.

In ordinary 3-d space, a flow can be described as a velocity field $\vec{v}(x, y, z)$. For each point, it defines a velocity at that point. This can also be a function of time.

- Incompressible fluid

- a given amount of the fluid always occupies the same volume. It also means that the density of the fluid—the number of molecules per unit volume—is uniform and stays that way forever.

Divergence of the vector field $\vec{v(t)}$, is defined to be,

$$ \nabla \cdot \vec{v} = \left( \frac{\partial{v_x}}{\partial{x}} + \frac{\partial{v_y}}{\partial{y}} + \frac{\partial{v_z}}{\partial{z}} \right) $$

So in the small cube, if velocity along all three axis remains constant, divergence is zero. Incompressible fluid will have zero divergence.

But, is the flow through phase space incompressible? Liouville’s Theorem says that yes, if the system satisfies Hamilton’s equations.

Example: $H = pq$

$$ \begin{align*} \dot{q} &= q \\ \dot{p} &= -p \end{align*} $$

The flow decreases exponentially in p axis, and increases exponentially in q axis. The blob changes the shape extremely, but volume remains constant.

Lioville’s theorem in quantum mechanics is replaced by unitarity.

Poisson Brackets#

Let $F(q, p)$ be the generic function of q’s and p’s. E.g., it could be potential energy, kinetic energy, angular momentum, etc.

As we follow a point in a phase space, we get a trajectory of F. i.e., F is a function of time.

$$ \begin{align} \dot{F} &= \sum_{i} \left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial q_i} \dot{q_i} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial p_i} \dot{p_i} \right) \\ \dot{F} &= \sum_{i} \left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial q_i} \frac{\partial H}{\partial p_i} - \frac{\partial F}{\partial p_i} \frac{\partial H}{\partial q_i} \right) \end{align} $$

For any two functions F, and G in a phase space, Poisson Bracket is defined as, $$ \{F, G\} = \sum_{i} \left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial q_i} \frac{\partial G}{\partial p_i} - \frac{\partial F}{\partial p_i} \frac{\partial G}{\partial q_i} \right) $$

Thus, $\dot{F}$ could be rewritten as $\{F, H\}$.

The time derivative of anything is a poisson bracket of itself with the Hamiltonian.

- $\dot{q_k} = \{q_k, H\} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p}$. (Simple application of the notation.)

- $\dot{p_k} = \{p_k, H\} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial q}$. (Simple application of the notation.)

Thus, Poisson bracket gives Hamilton’s equations back.