Quantum Mechanics Notes

Quantum Mechanics#

Differences from Classical Mechanics#

- States have different logical structure than CM.

- States and measurements are different unlike CM. e.g., Position and Momemntum can be determined by experiments in CM.

Spins#

Particles have properties attached to it. e.g., mass, electric charge.

Even a specific particle is not completely specified by its position.

Attached to electron is an extra degree of freedom, called spin. Spin is as quantum mechanical as it can and we should not try to visualize it.

Testing#

Propositions: $$ \begin{align*} A &: \sigma_z = +1 \\ B &: \sigma_x = +1 \\ \end{align*} $$

Classically,#

To test (A or B), one could first gently test $\sigma_z$. If it is -1, one would gently test $\sigma_x$. The result of doing it otherway (i.e., B or A) will be the same as doing (A or B). The reason is that classically, measurements are gentle. They don’t change the state of the system.

In Quantum Mechanics,#

If some entity prepares the spin in $\sigma_z = +1$ state, and we measure A or B (whether we use short circuit or not), we will measure it to be true. However, if we measure B or A, there is 25% chance that we will measure it to be false.

What about A and B? If we conclude that A and B is true, can we confirm it again? Answer is no. Since to compute B, we had to measure $\sigma_x$, which ruined measurement of A. Thus we can’t confirm it. i.e., experiment is not reproducible.

Complex Numbers#

Two ways to represent them.

In cartesian coordinates, $z = x + iy$.

In polar coordinates, $z = re^{i\theta}$.

$ x_1 x_2 = (r_1e^{i\theta_1})(r_2e^{i\theta_2}) = r_1 r_2 e^{i(\theta_1 + \theta_2)}$.

$z = x + iy = re^{i\theta}$

$z^\ast = x - iy = re^{-i\theta}$

$z^\ast z = r^2$, i.e., a real number

Phase Factors#

These are complex numbers whose r componenet is 1. Following holds for them,

$$ \begin{align} z^\ast z &= 1 \\ z &= e^{i\theta}\\ z &= \cos\theta + i \sin\theta \end{align} $$

$$\renewcommand{\bra}[1]{\left\langle{#1}\right|}$$ $$\renewcommand{\ket}[1]{\left|{#1}\right\rangle}$$ $$\renewcommand{\braket}[1]{\left\langle{#1}\right\rangle}$$

Vector Spaces#

Vector spaces is familiar concept from abstract linear algebra.

Complex Conjugate of space V#

For every $\ket{A}$ there exists $\bra{A}$ in conjugate space. This space has following properties.

- The conjugate of $\ket{A} + \ket{B}$ is $\bra{A}+\bra{B}$.

- Conjugate of $z\ket{A}$ is $z^\ast \bra{A} = \bra{A}z^\ast $.

In the concrete case where ket space is column vectors, bra space is denoted as row vectors.

i.e., if

$$ \begin{align*} \ket{A} = \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_1 \\ \alpha_2 \\ \vdots \\ \alpha_n \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$

then $$ \begin{align*} \bra{A} = \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_1^\ast & \alpha_2^\ast & \dots & \alpha_n^\ast \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*} $$

Inner Products#

Inner product is always between bras and kets. It is written like $\braket{B|A}$. The result is a complex numbers.

Axioms of inner product.#

- Inner product is linear. $\bra{C} + (\ket{A}+\ket{B}) = \braket{C|A} + \braket{C|B}$.

- $\braket{B|A} = \braket{A|B}^\ast $.

Special vectors#

- Normalized: $\braket{A|A} = 1$.

- Orhthogonal: $\braket{B|A} = 0$.

Orhtonormal Basis.#

Let our space be N dimensional. And let the orthonomal basis denoted by $\ket{i}$.

$$ \ket{A} = \sum_i \alpha_i \ket{i}, $$

where, $\alpha_j = \braket{j|A}$. (To derive this, multiply both sides by $\bra{j}$.)

States#

In CM, knowing the state means knowing everything that is necessary to predict the future.

In QM, knowing the state means knowing as much as can be known about how the system was prepared.

Apparatus $\cal{A}$ can be oriented on any axis. If we orient it along z axis, the measured spin will either be +1 or -1.

$\sigma_z = \pm 1$. We can denote +1 as state $\ket{u}$ and -1 as $\ket{d}$.

Similarly $\sigma_x = \pm 1$, can be denoted by $\ket{r}$ and -1 as $\ket{l}$. And $\sigma_y = \pm 1$, can be denoted by $\ket{o}$ and -1 as $\ket{i}$.

If two states are orthogonal then these two states can be determined together. For example, if $\sigma_z$ was prepared to be in $\ket{u}$, for any subsequent measurements the probability that $\ket{d}$ is detected is 0. Thus, for binary spin, the state space is two dimensional. For now we can take $\ket{u}, \ket{d}$ as the basis vectors.

Then, the generic state $\ket{A} = \alpha_u \ket{u} + \alpha_d \ket{d}$. Where $\alpha_i = \braket{i|A}$.

The meaning of,

- $\alpha_u^\ast \alpha_u$: If the spin was prepared in $\ket{A}$ state, $\alpha_u^\ast \alpha_u$ is the probability that $\sigma_z = +1$.

- $\alpha_d^\ast \alpha_d$: is the probability that $\sigma_z = -1$.

Since probabilities must add to 1, $\alpha_u^\ast \alpha_u + \alpha_d^\ast \alpha_d = 1$. It is equivalent to saying that $\ket{A}$ is normalized, i.e., $\braket{A|A} = 1$.

General principle of quantum systems: the state of a system is represented by a unit (normalized) vector in a vector space of states. Moreover, the squared magnitudes of the components of the state-vector, along particular basis vectors, represent probabilities for various experimental outcomes.

Representing $\ket{r}$ and $\ket{l}$ using above basis vectors#

We know that if A initially prepares the state in $\ket{r}$, $\sigma_z = \pm 1$ with equal probability. Hence, $\alpha_u^\ast \alpha_u =\alpha_d^\ast \alpha_d = \frac{1}{2}$. One choice is to have $\alpha_u = \alpha_d = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$.

$\ket{r} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{u} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{d}$. (There are is still ambiguity, called phase ambiguity.)

To solve for $\ket{l}$ the above process repeats. But, in addition, $\braket{l|r} = 0$. One choice is $[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}, -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}]$. But it is not the only choice. Even for fixed choice for $\ket{r}$, you can multiply above choice by a phase factor ($z = e^{i\theta}$), and still satisfy the two constraints. Later, we will find out that no measurable quantity is sensitive to the overall phase-factor, and therefore we can ignore it when specifying states.

Representing $\ket{i}$ and $\ket{o}$ using above basis vectors#

To solve for $\ket{i}$ and $\ket{o}$, we need same conditions as we needed above. But we also need additional constrains. For example, if A prepares the state in $\ket{i}$,$\sigma_x = \pm1$, with equal probability. Also $\braket{i|o} = 0$.

The following solution solves for these constraints (up to phase-factor ambiguity).

$\ket{i} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{u} + \frac{i}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{d}$.

$\ket{o} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{u} - \frac{i}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{d}$.

With the previous discussion, the vectors can be represented in column format as below.

$$ \begin{align*} \ket{u} &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \ket{d} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \\ \end{align*} $$

Matricies#

If we have a basis $\ket{i}$, a vector $\ket{A}$ can be rewritten as,

$$ \ket{A} = \sum_i \alpha_i \ket{i} = \sum_i \ket{i} \braket{i|A} $$.

Similarly, $$ \bra{A} = \sum_i \braket{A|i}\bra{i} $$.

Axiom: Physical observables are described by linear operators.

Observables are the things that we can measure. e.g., coordinates of a particle; the energy, momentum, or angular momentum of a system; or the electric field at a point in space.

$$ \begin{align*} M \ket{A} &= \ket{B} \\ M \sum_j \alpha_j \ket{j} &= \sum_j \beta_j \ket{j} \\ \sum_j \alpha_j M\ket{j} &= \sum_j \beta_j \ket{j} \text{;;assuming M is linear} \\ \sum_j \alpha_j \bra{k} M \ket{j} &= \sum_j \beta_j \braket{k|j} \text{;;multiply both sides by} \bra{k} \\ \sum_j \alpha_j m_{kj} &= \beta_k\\ \end{align*} $$

Note that each $m_{kj}$ is a complex number. We can think of M in terms of matrix (defined by a choice of basis vectors).

Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues#

$M \ket{\lambda} = \lambda \ket{\lambda}$. $\lambda$ is an eigenvalue, and $\ket{\lambda}$ is an eigenvector.

Linear operators on bra vectors#

$$ \begin{align*} \bra{B} &= \begin{bmatrix} b_1^\ast & b_2^\ast & b_3^\ast \end{bmatrix} \\ M &= \begin{bmatrix} m_{11} & m_{12} & m_{13} \\ m_{21} & m_{22} & m_{23} \\ m_{31} & m_{32} & m_{33} \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$

Than $\bra{B} M$ is just row vector multiplied by matrix M.

Hermitian Conjugate#

$$ \begin{align*} M^\dagger &= (M^T)^\ast \\ M \ket{A} &= \ket{B} \\ \bra{A} M^\dagger &= \bra{B} \\ \end{align*} $$

Hermitian Operators#

- Observables quantities in classcial mechanics are real numbers. i.e., they are their own complex conjugate.

- Observables in quantum mechanics (i.e., linear operators) are also their own complex conjugates. Such operators are called Hermitian Operators. $M^\dagger = M$.

Properties of Hermitian Operators#

- Their eigenvalues are real.

- Their eigenvectors form an orthonormal basis. (i.e., their eigenvectors are orthonormal and they form a basis)

Principles#

- The observable or measurable quantities of QM are represented by a linear operator L.

- The possible readings of the measurements are eigenvalues $\lambda_i$. The state for which reading is unambiguously $\lambda_i$ is the corresponding eigenvector $\ket{\lambda_i}$.

- Unambiguously distinguishable states are represented by orthogonal vectors. e.g., $\braket{u|d} = 0$.

- If $\ket{A}$ is the state vector of the system, and the observable L is measured, the probability of observing $\lambda_i$ is given by $\braket{A|\lambda_i}\braket{\lambda_i|A}$.

Since the readings (i.e., eigenvalues) are real and eigenvectors are orthogonal, the operator L must be hermitian.

P1 says that $\sigma_x, \sigma_y, \text{and} \sigma_z$ are identified with a specific linear operator in 2D space of states describing the states. P2 says that the actual measurments can take discrete values. e.g., energy of atom will be one of the established energy levels of the atom.

3-Vector Operator $\sigma$#

- Just as a spin-measuring apparatus can only answer questions about a spin’s orientation in a specific direction, a spin operator can only provide information about the spin component in a specific direction.

- To physically measure spin in a different direction, we need to rotate the apparatus to point in the new direction. The same idea applies to the spin operator—if we want it to tell us about the spin component in a new direction, it too must be “rotated” but this kind of rotation is accomplished mathematically.

Operator Matrices#

Using above four principles, and solving linear equations, we can derive them.

$$ \sigma_z = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix}, \sigma_x = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, \sigma_y = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{bmatrix} \text{.} $$

These along with Identity matrix are called Pauli Matrices.

IMPORTANT: Applying the operator L to state $\ket{A}$ does not change the state to $L\ket{A}$. $L\ket{A}$ is actually a supuerposition and tells us the probabilities of basis states. When we actually measure using L, the system is changed to one of the eignestates unambiguously.

There is nothing special about these three operators. We can take any direction $\hat{n} = (n_x, n_y, n_z)$, orient the apparatus A along $\hat n$, activate A, and measure the component of the spin along $\hat n$. That means there has to be an operator that represents this operation. Indeed, this operator is given by $\sigma_n = \sigma \cdot \hat n$, where $\sigma = (\sigma_x, \sigma_y, \sigma_z)$.

$$ \sigma_n = \begin{bmatrix} n_z & (n_x - i n_y) \\ (n_x + i n_y) & -n_z \end{bmatrix} $$

Spin-Polarization Principle#

For any state $\ket{A} = \alpha_u \ket{u} + \alpha_d \ket{d}$, there exists some direction $\hat n$ such that $\sigma \cdot \hat n = \ket{A}$.

States of the spins are characterized by a polarization vector, and along the polarization vector the component of the spin is predictably +1.

General spin state is $cos(\frac{\beta}{2}) \ket{u} + e^{i\phi} sin(\frac{\beta}{2}) \ket{d}$.

Time Development Operator#

Let the closed system be in state $\ket{\Psi(t)}$. Thus, state can be different at different times.

The time development operator $U(t)$ tells us how the system evolves with time.

$$\ket{\Psi(t)} = U(t) \ket{\Psi(0)}$$.

Thus, the time evolution of the state is deterministic.

Quantum mechanics assumes,

- that U(t) is a linear operator.

- If two states are orthonormal, they remain orthonormal in the evolution. i.e., $\braket{\Psi(0)|\Phi(0)} =0 \implies \braket{\Psi(t)|\Phi(t)} = 0$.

As a consequence of these two assumptions, it is easy to prove that $U(t)^{\dagger}U(t) = I$. Such operator is called unitary operator.

Principle 5: Time evolution of state vectors is unitary.

Unitarity also implies that as time evolves, the overlap (inner product) between two states remains the same.

Quantum Mechanics also assumes that time evolution is continuous.

Thus, for small time $\epsilon, U(\epsilon) = I - i \epsilon H$. Using the unitarity condition $U(t)^{\dagger}U(t) = I$, we can show that $H^{\dagger} = H$.

Thus, H is hermitian. i.e., it is an obeservable, and has complete set of orthonormal eigenvectors.

We will see that, the eigenvalues of H are the values that result from measuring the energy levels of the quantum system. Thus, it has resemblance to the hamiltonian from the classical mechanics.

Using the continuity assumption inside $\ket{\Psi(t)} = U(t) \ket{\Psi(0)}$, we can derive,

$$ \frac{d \ket{\Psi}}{dt} = -iH\ket{\Psi}$$.

This equation is known as Generalized Schrodinger equation or time-dependent schrodinger’s equation. If we know the Hamiltonian of the system, we can know how the state of the undisturbed system evolves with the time.

Plank’s constant#

h = 6.6 * 1e-34 kgm^2/s1.

$\hbar = \frac{h}{2\pi} = 1.054571726 \dots x 10^{-34} \frac{kgm^2}{s}$

In the gen. schrodinger’s eqn, lhs has units of 1/time, whereas rhs has units of energy (kgm^2/s^2, because H is hamiltonian). This is wrong. However multiplying lhs by Plank’s constant, units are proper. Thus, the correct Generalized schrodinger’s equation is $$ \hbar \frac{d \ket{\Psi}}{dt} = -iH\ket{\Psi}$$.

Expectation#

If L is an observable, the expectation is defined as $\braket{L} = \sum_i P(\lambda_i) \lambda_i$.

When state of the system is $\ket{A} = \sum_i \alpha_i \lambda_i$, the expecation can be computed as $\braket{L} = \sum_i \alpha_i^\ast \alpha_i \lambda_i = \braket{A|L|A}$.

Try to apply this for state $\ket{r}$ and observable =$\sigma_z$. The arithmetic should result in value 0.

Effect of the phase factor.#

We can multiply the state vectors by a phase factor $e^{i\theta}$ for any $\theta$. This does no make any difference. Although, probability amplitude will change i.e., $\alpha_i \to e^{i\theta} \alpha_i$, the probability does not change, i.e., $\alpha_i^\ast \alpha_i$ remains unchanged. Similarly, the expectation of the observable does not change.

Change in the expectation#

$\frac{d \braket{\Psi(t)|L|\Psi(t)}}{dt} = \braket{\dot\Psi(t)|L|\Psi(t)} + \braket{\Psi(t)|L|\dot\Psi(t)}$. Using generalized schrodinger’s equations,

$\frac{d \braket{\Psi(t)|L|\Psi(t)}}{dt} = \frac{i}{\hbar} \braket{\Psi(t)|HL - LH|\Psi(t)}$.

Linear operators don’t commute, so HL != LH.

Commutator: Given two operators L, and M, LM - ML is called the commutator of L with M, and is denoted by [L, M]. Note that [L, M] = -[M, L].

Thus, $\frac{d}{dt} \braket{L} = \frac{-i}{\hbar} \braket{[L, H]}$.

It is easy to prove that $i[L, H]$ is also Hermitian. Thus, a valid observable.

This has resemblance to classical mechanics. $\dot{F} = \{F, H\}$.

Conservation in quantum mechanics#

To say that an observable Q is conserved is to say that expected value $\braket{Q}$ does not change with time. A stronger condition is that any moment $\braket{Q^m}$ does not change with time.

$\braket{Q}$ does not change ammounts to $[Q, H] = 0$. That is Q commutes with H. Using the properties of commutator, it is easy to prove that $[Q^m, H] = 0$ for any $m \ge 1$.

It turns out that if $[Q, H] = 0$ then for any function of Q, $[f(Q), H] = 0$.

H is also conserved, as $[H, H] = 0$. H is defined to be the energy of the quantum system.

Solving Schrodinger’s equation#

Time dependent Schrodinger’s equation is $ \hbar \frac{d \ket{\Psi}}{dt} = -iH\ket{\Psi}$.

Since H represents enrgy, the oberservable values of energy are eigenvalues of H. Call them $\ket{E_j}$ and $E_j$.

$$ H \ket{E_j} = E_j \ket{E_j} $$

These are call time-independent schrodinger’s equations.

We can write $\ket{\Psi{(t)}} = \sum_j \alpha_j(t) \ket{E_j}$.

Thus, $\ket{\dot\Psi{(t)}} = \sum_j \dot\alpha_j(t) \ket{E_j}$.

Using time-dependent Schrodinger’s equation, we can solve for $\dot\alpha_j(t)$. It has the form $\dot\alpha_j(t) = -\frac{i}{\hbar}E_j \alpha_j(t)$. Which has the solution $\alpha_j(t) = \alpha_j(0) e^{\frac{-i}{\hbar} E_j t}$.

But, $\alpha_j(0) = \braket{E_j|\Psi(0)}$.

So, $\Psi(t) = \sum_j \ket{E_j}\braket{E_j|\Psi(0)} e^{-\frac{i}{\hbar}E_j t}$.

General Recipe#

- Get the H somehow.

- Find the $\ket{E_j}$ and $E_j$.

- Prepare the system in initial state $\Psi(0)$.

- Use above solution to find the state at any later time.

- If you have some other operator L, you can “predict” the outcome of measuring future state using the eigenvectors of L. i.e., the probability the outcome of measuring L is $\lambda_i$ is precisely $|\braket{\lambda_i|\Psi(t)}|^2$.

Complex systems#

There are systems for which there are more than two observables, and they all can be measured simultaneously. Single spin is not such system. Though there are three observables $\sigma_{\{x,y,z\}}$. Only one of them can be observed at a time.

Particle moving in three dimensions, all three dimensions x, y, and z can be measured simultaneously.

Other such system is a system of two particles. Let’s denote these two observables as L and M. If we measure both spins, we leave the system in a state which is simultaneously eigenvector of both L and M. Let the eigenvectors of L be denoted as $\lambda_i$ and same for M with $\mu_a$.

In order to have simultaneous eigenvectors $\ket{\lambda, \mu}$, L and M must commute with each other. i.e., $LM \ket{\lambda, \mu} = ML\ket{\lambda, \mu}$. i.e., $[L, M]\ket{\lambda, \mu} = 0$. Since this statement is true of any basis eigenvector $\ket{\lambda, \mu}$, we know that $[L, M] = 0$.

Thus, if we have complete basis of simultaneous eigenvectors, the observables commute. Converse is also true. If observables commute, they have a complete basis of simultaneous eigenvectors. This statement is true for any number of observables in the system, and not just two.

Suppose, we have a basis of states $\ket{a,b,c, \dots}$ for some complex system.

$$\ket{\Psi} = \sum_{a,b,c,\dots} \psi{(a,b,c, \dots)} \ket{a,b,c, \dots}$$

Where, $\psi{(a,b,c, \dots)} = \braket{a,b,c, \dots|\Psi}$. This $\psi$ is called a wave function.

$P(a,b,c, \dots) = \psi^\ast{(a,b,c, \dots)} \psi{(a,b,c, \dots)}$. This is the probability of observing the value $a,b,c,\dots$ of commuting observables $A,B,C,\dots$.

If a state is an eigenvector of operator A, which does not commute with B, then it will not be an eigenvector for B. Thus, if A and B don’t commute, there will be uncertainity in either A or B if not both.

Quantifying Uncertainty#

The system is in state $\ket\Psi$. We want to observe some A. A can be thought as a random variable. The possible outcomes are eigenvalues of A, with predefined probabilities. Thus $\braket{A}$ is well defined, and is the expected value of A. We can also find the variance of A! This quantifies the uncertainty of A.

First define $\bar{A} = A - \braket{A}I$. This is also an Hermitian operator, so has real eigenvalues. If $a$ is an eigenvalue of A, $\bar{a} = a - \braket{A}$ is an eigenvalue of $\bar{A}$.

Thus the variance, denoted as $(\Delta A)^2 = \sum_a \bar{a}^2 P(a)$.

A little bit of algebra shows that this is equivalent to $\braket{\bar{A}^2} = \braket{\Psi|\bar{A}^2|\Psi}$.

Uncertainty Principle#

From triangle inequality $|x| + |y| \ge |x+y|$, one can derive $2|x||y| \ge |\braket{x|y} + \braket{y|x}|$. (Hint: Square both sides, and expand).

Putting, $x = A\ket\Psi$ and $y = iB\ket\Psi$, we get $\Delta{A} \Delta{B} \ge \frac{1}{2} | \braket{\Psi|[A, B]|\Psi}$. (Hint: Though formula is true in general, it is easy to derive by assuming that $\braket{A} = \braket{B} = 0$, in which case $(\Delta{A})^2 = \braket{A^2}$.)

Composite System#

Atom is made of nucleons and electrons, each is a quantum system of it’s own. We want to study composite system.

For the moment we assume there are two systems, A and B (a.k.a. Alices’s sytem and Bob’s sytem, respectively). A has states from staet space $S_A$, which has dimensionality of $N_A$. Same for system B.

The combined system has statespace $S = S_A \otimes S_B$, which has dimensionality $N_A N_B$. $\otimes$ is a tensor product. The states of S are denoted as $\ket{ab}$, where $a \in S_A$ and $b \in S_B$.

If an operator M acts on the states of the composite system, M has $N_A N_B$ rows and colums. The entry $M_{a’b’, ab}$ is given by $\braket{a’b’|M|ab}$.

If A, and B are 2x2 matrices, their product is defined as $$\left[\begin{matrix}A_{11} B_{11} & A_{11} B_{12} & A_{12} B_{11} & A_{12} B_{12}\\ A_{11} B_{21} & A_{11} B_{22} & A_{12} B_{21} & A_{12} B_{22}\\ A_{21} B_{11} & A_{21} B_{12} & A_{22} B_{11} & A_{22} B_{12}\\ A_{21} B_{21} & A_{21} B_{22} & A_{22} B_{21} & A_{22} B_{22}\end{matrix}\right] $$

The basis vectors $\ket{ab}$ are taken to be orthonormal. $\braket{ab|a’b’} = [a = a’, b = b’]$.

Thus, any state in the composite system is written as $\ket\Psi = \sum_{a,b} \psi(a, b) \ket{ab}$.

Two Spin System#

Let’s have four state vectors $\ket{uu}, \ket{ud}, \ket{du}, \ket{dd}$.

Product State#

A product state is the result of completely independent preparations of two spins, each with its’ own apparatus to prepare a spin. If the state is not a product state than it is entangled.

Suppose spin A is prepared in $\alpha_u \ket{u} + \alpha_d \ket{d}$ and B is prepared in $\beta_u \ket{u} + \beta_d \ket{d}$ Where $\alpha^\ast_u \alpha_u + \alpha^\ast_d \alpha_d = \beta^\ast_u \beta_u + \beta^\ast_d \beta_d = 1$. In such case we need 4 real parameters to define the state (2 for each spin).

Thus, the combined product state is written as $\{\alpha_u \ket{u} + \alpha_d \ket{d} \} \otimes \{ \beta_u \ket{u} + \beta_d \ket{d} \}$. This can be expanded, to rewrite in the basis vectors of the combined system, as $\alpha_u \beta_u \ket{uu} + \alpha_u \beta_d \ket{ud} + \alpha_d \beta_u \ket{du} + \alpha_d \beta_d \ket{dd}$.

The main feature of a product state is that each subsystem behaves independently of the other.

General Tensor product space.#

The general space is written as $\psi_{uu} \ket{uu} + \psi_{ud} \ket{ud} + \psi_{du} \ket{du} + \psi_{dd} \ket{dd}$. Unlike product space, we need 6 real parameters (8(to define complex numbers) - 1 (normalization) - 1(phase factor)).

Thus, there has to be some states which can not be written as product state. Singlet, and triplets are such states.

Singlet: $\ket{sing} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{ud} - \ket{du})$.

Triplets:

- $T_1 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{ud} + \ket{du})$.

- $T_2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{uu} + \ket{dd})$.

- $T_3 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{uu} - \ket{dd})$.

It is easy to prove that these states can’t be written as product states. (Hint: for product state you have to show that $\alpha_x \beta_y = c$, but this will be impossible as some other requirement $\alpha_x \beta_w = 0$ or $\alpha_z \beta_y = 0$ will be violated.)

These states are maximally entangled.

Observables in combined system.#

The observables in the case of single sping system, still apply in the combined system. They just modify their half.

e.g., if $\sigma_x$ is observable of spin A, $\sigma_x \ket{ud} = \ket{dd}$.

Note that $\sigma_x$ for single spin system and $\sigma_x$ for combined systems are different operators. This is easy to see in the matrix forms. The two matrices are different.

In the case of single spin system (or product state), there is a direction where the measurement is guaranteed to be +1. Thus, $\braket{\vec{\sigma} \cdot \vec{n}} = \braket{\Psi|\vec{\sigma} \cdot \vec{n}|\Psi} = 1$, for that particular $\vec{n}$. Thus we know that none of the $\braket{\sigma_x}, \braket{\sigma_y}, \braket{\sigma_z}$ can be zero(which would lead to contradiction).

On the other hand, if you compute $\braket{\sigma_x}$ for $\ket{sing}$, you will find it to be zero. In fact, for singlet state, $\braket{\sigma_x} = \braket{\sigma_y} = \braket{\sigma_z} = 0$. Since the components are zero on expectation, we are equaly likely to get +1 and -1 for any measurement. Thus, although the state is known, we don’t know the outcome.

The operators that act on the two separate factors commute with one another.

The operator $\tau_z \sigma_z$, is a product of two oprators. Little math tells us that $\ket{sing}$ is an eigenvector for $\tau_z \sigma_z$. $\tau_z \sigma_z \ket{sing} = -\ket{sing}$. This means that the product of observations is always -1. Thus both measurements always have opposite signs. In fact, $\ket{sing}$ is also an eigenvector for operators $\tau_x \sigma_x$ and $\tau_y \sigma_y$, with eigenvalue -1.

On the other hand if you try to compute $\braket{\tau_x \sigma_y}$, you will find that to be 0.

For the triplets:

| $\ket{sing}$ | $\ket{T_1}$ | $\ket{T_2}$ | $\ket{T_3}$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\braket{\sigma_z \tau_z}$ | -1 | -1 | +1 | +1 |

| $\braket{\sigma_x \tau_x}$ | -1 | +1 | +1 | -1 |

| $\braket{\sigma_y \tau_y}$ | -1 | +1 | -1 | +1 |

Thus, singlet and triplets are eigenvalues for the product operators.

$\vec{\sigma} \cdot \vec{\tau}$ is an observable that can not be measured by measuring two spins by individual apparatuses. How can we measure such thing? Some atoms have spins. When two of these atoms are close to each other (e.g., in a lattice), in some situations their Hamiltonian is proportional to $\vec{\sigma} \cdot \vec{\tau}$.

The four vectors above are eigenvectors for $\vec{\sigma} \cdot \vec{\tau}$. The singlet has eigenvalue -3 and each triplet has eigenvalue +1.

Comment: Generating singlet state is easy. Two spins prefer to be anti-aligned. Now bring these two spins together, they will radiate a photon and result in this state, as this state has low energy.

For product state it is easy to prove $\braket{AB} = \braket{A} \braket{B}$. Thus, we can see that $\braket{\sigma_w \tau_w}$ can not be product states. Because for them $\braket{\sigma_w} = 0$.

Outer Products#

$\ket{\Psi} \bra{\Phi}$ is an operator. Which can be applied to bras or kets.

$\ket{\Psi} \bra{\Phi} \ket{A} = \ket{\Psi} \braket{\Phi|A}$

Specificaly if $\ket\Psi$ is normalized, Projection Operator is defined as $\ket{\Psi}\bra{\Psi}$.

Properties of Projection Operators.

- They are Hermitian.

- $\Psi$ is an eigenvector with eigenvalue +1.

- All perpendicular vectors to $\Psi$ are eigenvectors with eigenvalue 0.

- Square of projection operator is the projection operator itself. $(\ket\Psi \bra\Psi)^2 = \ket\Psi \bra\Psi$.

- Trace($Tr(L) = \sum_i \braket{i|L|i})$ of projection operator is 1.

- If we add all proj. operators for all basis vectors we get identity operator. $\sum_i \ket{i}\bra{i} = I$.

- Expectation of any operator L, for state $\Psi$ is $Tr (\ket\Psi \bra\Psi L)$.

Density Matrix#

Suppose we don’t know the exact state of the system, but we know that it is either $\Psi$ of $\Phi$ with equal probability. Then, the expected value is $ \frac{\braket{\Psi|L|\Psi} + \braket{\Phi|L|\Phi}}{2}$. If we define a new operator $\rho = \frac{1}{2}\ket\Psi \bra\Psi + \frac{1}{2} \ket\Phi \bra\Phi$, the expected value can be computed as $Tr (\rho L)$.

The definition for $\rho$ is general, and holds for more than two states. On the other hand, if we knew exactly that the state is $\Psi$, the last property of the projection operator still applies. In any case, $\braket{L} = Tr (\rho L)$.

In a pure state, density matrix is just a projection operator. In a mixed state, it is a combination of multiple projection operators.

In the matrix form, for particular basis, $\rho_{aa’} = \braket{a|\rho|a’}$. In this basis, $\braket{L} = \sum_{a,a’} \rho_{aa’} L_{a’a}$.

In classical system, two particles in a line for example, if we know state of the complete system (i.e., $x_1, x_2, p_1, p_2$), we know the state of the constituents (i.e., $x_1, p_1$ and $x_2, p_2$). (Comment: This is classical pure state. But, sometimes we don’t know the exact $x_1, x_2, p_1, p_2$, but have some distribution of $\rho(x_1, x_2, p_1, p_2)$. This is mixed state.)

This is not true in QM when there is entanglement. In such cases, even if the combined system can be in pure state $\psi(a,b)$, each of it’s constituent states must be described by a mixed state (unlike classical setting).

Say we have the full knowledge of the combined system(A, B). That is we know $\psi(a, b)$ of the combined system. And we want to know what we can about A. Let’s pick an operator L which only acts on A.

Here, $\braket{L} = \sum_{ab, a’b’} \psi^{\ast}{(a’b’)} L_{a’b’, ab} \psi{(ab)}$.

Using the rules of matrix construction(Kronecker Product), $L_{a’b’, ab} = L_{a’a} \delta_{b’b}$.

Thus, $$ \begin{align*} \braket{L} &= \sum_{a, b, a’} \psi^{\ast}{(a’b)} L_{a’a} \psi{(ab)} \\ &= \sum_{a, a’} L_{a’a} \sum_{b}\psi^{\ast}{(a’b’)} \psi{(ab)} \\ &= \sum_{a, a’} \rho_{aa’} L_{a’a} \psi{(ab)} \\ \end{align*} $$

Where, we defined $\rho_{aa’} = \sum_{b}\psi^{\ast}{(a’b)} \psi{(ab)}$.

Note the difference in the definition of the $\rho$s. If in the above equation, we had product state (i.e., non entangled state $\psi(a, b) = \psi(a) \phi(b)$), we will get $\rho_{aa’} = \psi^{\ast}{(a’)} \psi{(a)} \sum_{b}\phi^{\ast}{(b)} \phi{(b)} = \psi^{\ast}{(a’)} \psi{(a)}$. Thus, we get our projection operator (i.e., pure state density matrix) back.

But in general, even if we had pure state for combined system ($\psi(a, b)$), we may not get pure state for constituent system.

For a single spin system, with pure state, the density matrix looks like below.

$$\left(\begin{matrix} \alpha^\ast \alpha && \alpha \beta^\ast \\ \alpha^\ast \beta && \beta^\ast \beta \end{matrix}\right) $$

Properties of Density Matrix#

- Diagonal entries tell us the probability of the observation. That is, $P(a) = \rho_{aa}$. This is in line with traditional probability theory. The probability of observing eigenvalues for a, b is $P(a, b) = \psi^\ast(ab) \psi(ab)$. Marginalizing out b gives us $P(a) = \sum_b \psi^\ast(ab) \psi(ab)$. This is also easy to see in the density matrix for pure state shown above.

- Density matrix is Hermitian.

- Trace of density matrix is 1.

- All Eigenvalues are between 0 and 1 inclusive. Since the trace is 1, if one eigenvalue is 1, the rest are 0.

- For a pure state, $\rho^2 = \rho$ and $Tr(\rho^2) = 1$.

- For a mixed or entangled state, $\rho^2 \ne \rho$ and $Tr(\rho^2) < 1$.

Proving 5 is easy. Simple algebra. But, I found proving 6 to be little bit difficult. So here is the proof.

Proof for point 6

We will first prove that $Tr(\rho^2) < 1$.

Assume that our mixed state is $\sum_i p_i \ket{i} \bra{i}$.

$$ \begin{align*} \rho^2 &= \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j \ket{i} \bra{i} \ket{j} \bra{j} \\ &= \sum_{i,j} p_i p_j \braket{i|j} \ket{i} \bra{j} \\ Tr(\rho^2) &= \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j \braket{i|j} Tr(\ket{i} \bra{j}) \text{ // linearity of trace} \\ &= \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j \braket{i|j} \sum_k (i_k j^\ast_k) \\ &= \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j \braket{i|j} \braket{j|i} \\ &= \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j |\braket{i|j}|^2 \\ &< \sum_{i, j} p_i p_j \text{ //Cauchy Schwarz Inequalty} \\ &= \sum_i p_i \sum_j p_j \\ &= 1 \blacksquare \end{align*} $$

Now, $\rho^2 = \rho$ would imply that $Tr(\rho^2) = Tr(\rho) = 1$. Which contradicts what we just proved. So $\rho^2 \ne \rho$.

Some facts used in this proof are,

- Trace is a linear operator.

- Cauchy-Swartz Inequality $ |\braket{i|j}|^2 \le \braket{i|i} \braket{j|j}$ Moreover, equality holds only when both vectors are linearly dependent.

Examples of Density matrix (Exercise 7.8)

- $\ket{\Psi_1} = \frac{1}{2}(\ket{uu} + \ket{ud} + \ket{du} + \ket{dd})$ Density matrix for system A

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} \frac{1}{2} && \frac{1}{2} \\ \frac{1}{2} && \frac{1}{2} \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

Density matrix for system B

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} \frac{1}{2} && \frac{1}{2} \\ \frac{1}{2} && \frac{1}{2} \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

For both the systems $\rho^2 = \rho$. So is pure state.

- $\ket{\Psi_2} = \frac{1}{\sqrt2}(\ket{uu} + \ket{dd}) $

Density matrix for system A

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} \frac{1}{2} && 0 \\ 0 && \frac{1}{2} \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

Density matrix for system B

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} \frac{1}{2} && 0 \\ 0 && \frac{1}{2} \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

For both the systems $\rho^2 \ne \rho$. So is mixed state.

- $\ket{\Psi_3} = \frac{1}{5}(3\ket{uu} + 4\ket{ud})$

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} 1 && 0 \\ 0 && 0 \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

Density matrix for system B

$$ \left(\begin{matrix} \frac{9}{25} && \frac{12}{25} \\ \frac{12}{25} && \frac{16}{25} \\ \end{matrix}\right) $$

For both the systems $\rho^2 = \rho$. So is pure state.

Test for entanglement#

We have a wave function $\psi(a, b)$, and we want to test if that state is entangled or not.

Correlation Test#

Say there are two observables A and B, for two systems. The correlation between them is defined as $C(A, B) = \braket{AB} - \braket{A} \braket{B}$.

If a system is any state for which $C(A, B) \ne 0$, the state is entangled.

Using Density Matrix#

Theorem: For any product state, the density matrix of any constituent subsystem has exactly one non-zero eigenvalue (thus it has to be 1). Moreover, the eigenvector for this eigenvalue is the factor wave function for that subsystem.

E.g., if A’s wave function is $\psi$, and B’s wave function is $\phi$, such that $\psi(a, b) = \psi(a) \phi(b)$, $\psi$ is the eigenvector with eigenvalue 1 for A’s density matrix.

Conversly, if there are at least two eigenvalues($\lambda_j > 0, \lambda_k > 0$ (and since the Trace = 1, they are less than 1), one can prove that $\rho^2 \ne \rho$. And since $\rho^2 = \rho$ is necessary and sufficient condition for product state, we know that the state must be entangled.

Proof that at least two positive eigenvalues implies $\\rho^2 \\ne \\rho$.

Proof by contradiction.Assume $\rho^2 = \rho$.

$$ \rho^2 - \rho = 0 = \sum_i (\lambda_i^2 - \lambda_i) \ket{\Psi_i} \bra{\Psi_i} $$

Since, in particular $\lambda_k^2 - \lambda_k < 0$ and $\Psi_i$ are eigenbasis,

$$ \begin{align*} \braket{\Psi_k|0|\Psi_k} = 0 &= \sum_i (\lambda_i^2 - \lambda_i) \braket{\Psi_k|\Psi_i} \braket{\Psi_i|\Psi_k} \\ &= \lambda_k^2 - \lambda_k \\ &< 0 \end{align*} $$

Which is a contradiction.

In a maximally entangled state, all the eigenvalues of the density matrix are equal. $\rho_{aa} = \frac{1}{N_A}$, where $N_A$ is the number of states in subsystem A. Although in such state we don’t know anything about one particular subsystem (uniform probability distribution), there is correlation. If we measure one subsytem, we know the outcome of the experiment on other subsystem.

Continuous Domain#

So far we have talked about discrete case, where observable was discrete. There are observables like position which are continuous.

Our wave function is discrete complex-valued function. $\psi(\lambda)$, where for spin $\lambda$ was either up or down. The state $\Psi$’s wave function depended upon the basis. In the up-down basis $\Psi = \psi(\ket{u}) \ket{u} + \psi(\ket{d}) \ket{d}$.

For cases like particle moving on a line (x-axis), we need wave function that is continuous. We can write it as $\psi(x)$, where x is a real number. Notice that functions like this also form a vector space. Two functions can be added. It can be multiplied with a complex number to get another function, and so on.

- Inner Product

- $\braket{\Phi|\Psi} = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \phi^\ast(x)\psi(x) dx$

- Probability Density

- $P(x) = \psi^\ast(x) \psi(x)$ is NOT the probability of observing x. It is instead a density around x.

- Dirac Delta Function

- $\delta$ is defined such that $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \delta(x - x’) F(x’) dx’ = F(x)$.

Integration By Parts#

$ FG |_a^b - \int_a^b G dF = \int_a^b F dG$.

Generally $F \to 0 \text{ as } |x| \to \infty$ for wave functions to be properly normalized. And same for G. So $FG |_a^b = 0$ in such cases. So the formula is quite easy to remember in QM.

$$- \int_{-\infty}^\infty G \frac{dF}{dx} dx = \int_{-\infty}^\infty F \frac{dG}{dx} dx$$

Move the differentiation to another function by changing the sign.

Linear Operators#

- X : Multiply by x operator, $X \psi(x) = x \psi(x)$.

- D : Diffrentiation operator, $D \psi(x) = \frac{d \psi(x)}{dx}$.

- P : $P = -i \hbar D$.

Hermitian Operators.#

L is Hertmitian if $\braket{\Psi|L|\Phi} = \braket{\Phi|L|\Psi}^\ast$.

Since x (domain of $\psi, \phi$) is real, it is easy to show that “Multiply by X” $X$ operator is Hermitian.

On the other hand, you will find that D is not Hermitian. $\braket{\Psi|D|\Phi} = - \braket{\Phi|D|\Psi}^\ast$. Operators like this (where $D^\dagger = -D$ are called anti-hermitian. For any anti-hermitian operator A, both $iA$ and $-iA$ are hermitian.

Thus, we define an operator $P = -i \hbar D$ such that $-i \hbar D \ \psi(x) = -i \hbar \frac{d\psi(x)}{dx}$. This operator is Hermitian.

Particle State#

Formal Prose#

In classical mechanics, for a particle moving on x-axis, if the Hamiltonian equations are known, given (x, p) (i.e., position, and momenta p = mv) we know the flow in the phasespace.

However, decades of experience tells us that in Quantum Mechanics, one does not have states where both the components are specified. We know from experience that x AND p is not knowable, but x OR p can be known.

Details#

Since position, and momentum are observable, they would have Hermitian Operators associated with them. For position, this operator is X.

Eigenvalues, and Eigenvectors for X.#

Trying to solve the eigenvalue equation,

$$ \begin{align*} x \psi(x) &= x_0 \psi(x) \\ (x - x_0)\psi(x) &=0 \end{align*} $$

This holds true for all possible values of x. When $x \ne x_0$, this means that $\psi(x) = 0$. At $x = x_0$ it can take non zero value. We know such function, it is Dirac’s Delta function, $\delta(x - x_0)$.

Thus every $x’ \in \mathbb{R}$ is an eigenvalue for X, with eigenfunction $\delta(x - x’)$.

$\braket{x_0|\Psi} = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \delta(x-x_0) \psi(x) dx = \psi(x_0)$.

Thus $\braket{x|\Psi} = \psi(x)$.

Wave function in the position representation: is denoted as $\psi(x)$ and is the projection of the state on the eigenvectors for position, i.e., $\braket{x|\Psi} = \psi(x)$.

Eigenvalues, and Eigenvectors for P, the Momentum Operator#

NOTE: Connection with classical mass times velocity will become clear later.

If we solve for eigenvalue equation, $P \psi(x) = -i \hbar D \psi(x) = p \psi(x)$, we get the solution $\psi_p(x) = A e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$. Subscript p denotes the eigenfunction associated with eigenvalue p. The A is a normalizing constant, required to make the integration 1. It turns out to be, $A = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}}$. Note that, this eigenfunction is written in basis of position.

Thus,

$\braket{x|p} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$

And, $\braket{p|x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{\frac{-ipx}{\hbar}}$.

Waves?#

The momentum function $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$ has sin and cosine. The A–the constant– is not important in the frequency of the wave, it just changes the mangnitude. $e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$ has a wavelength of $\frac{2 \pi \hbar}{p}$. (Because: $e^{\frac{ip(x+\lambda)}{\hbar}} = e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}} e^{i 2 \pi} = e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$).

In 20th century, scientists wanted to detect smaller and smaller particles. One can’t resolve objects much smaller than the wavelength one using to look at them. So in 20th century, scientists wanted to find light of smaller and smaller wavelengths. We will later see that light of a given wavelength is composed of photons whose momentum is related to the wavelength by the relation $\lambda = \frac{2 \pi \hbar}{p}$. But, as per this relation, to get smaller wavelength, one must increase the momentum. This requires high energy. Hence, particle acclerators were/are required.

Momentum Basis#

We saw the eigenfunction associated with momentum operator was a function of x! That is because we wrote it in position basis. If for the state $\Psi$, we want to measure it’s momentum, we can do so by using the probability density function $\psi^\ast(p) \psi(p)$. $\psi(p)$ (not to be confused with $\psi(x)$) is a function of p. In the momentum basis it is just $\braket{p|\Psi}$.

Both wave function $\psi(x)$ and $\psi(p)$ represent the same state $\Psi$, just in different basis. It is possible to convert between two using fourier transform.

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(p) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int e^{\frac{-ipx}{\hbar}} \psi(x) dx \\ \psi(x) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}} \psi(p) dp \\ \end{align*} $$

Derivation of the transform

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(p) &= \braket{p|\Psi} \\ &= \braket{p\left|\int dx \ket{x}\bra{x} \right| \Psi} \\ &= \int dx \braket{p|x}\braket{x|\Psi} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int e^{\frac{-ipx}{\hbar}} \psi(x) dx \\ \psi(x) &= \braket{x|\Psi} \\ &= \braket{x\left|\int dp \ket{p}\bra{p} \right| \Psi} \\ &= \int dp \braket{x|p}\braket{p|\Psi} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}} \psi(p) dp \end{align*} $$

Relation with Poisson Brackets#

earlier we show that $[L, M] = i\hbar\{L, M\}$.

We can compute the commutator $[X, P] = XP - PX$.

$$ \begin{align*} XP \psi(x) &= -i \hbar x \frac{d \psi(x)}{dx} \\ PX \psi(x) &= -i \hbar \frac{d x \psi(x)}{dx} \\ &= -i \hbar x \frac{d \psi(x)}{dx} - i\hbar \psi(x) \\ [X, P]\psi(x) &= i \hbar \psi(x) \\ [X, P] &= i \hbar \end{align*} $$

Thus, the commutator is a number, which is non-zero. That is, X and P don’t commute. You can’t measure one without disturbing the other.

This also implies that Poisson bracket {X, P} = 1. This was proved in classical mechanics course. This is the link between classical momentum and quantum momentum P.

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle#

Earlier we had derived $\Delta{A} \Delta{B} \ge \frac{1}{2} |\braket{\Psi|[A, B]|\Psi}|$.

Thus, $\Delta{X} \Delta{P} \ge \frac{1}{2} |\braket{\Psi|[X, P]|\Psi}| = \frac{1}{2} \hbar$.

Let’s look at example. I think this section requires more mathematical rigor, but I am not at the point where I can justify much of what I am writing.

Let’s assume that our state is eigenstate of the momentum. That is, $\psi(p_0) = \delta (p-p_0)$. Then, as per Fourier formulas, $$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}} \psi(p) dp \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}} \delta(p-p_0) dp \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{\frac{i p_0 x}{\hbar}} \\ \psi^\ast(x) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{\frac{-i p_0 x}{\hbar}} \\ \psi^\ast(x)\psi(x) &= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \end{align*} $$

Thus, the density function for position is as uncertain as it can get, it is uniform.

In this case, there is no uncertainty in $\Delta P$. That is $\Delta P = 0$. However, $\Delta X = \infty$. Obviously, the product is not defined. But, maybe in the limits the product is greater than $\hbar /2$?

See discussion at https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/553145/does-the-heisenbergs-uncertainty-equation-holds-when-one-of-the-observable-have.

Time Evolution of Particles#

Simple Example#

Recall that time evolution of particle is given by generalized Schrodinger’s equation $i\hbar \frac{\partial \psi(x, t)}{\partial t} = H \psi(x, t)$. Where H is Hamiltonian, and is energy of the quantum system.

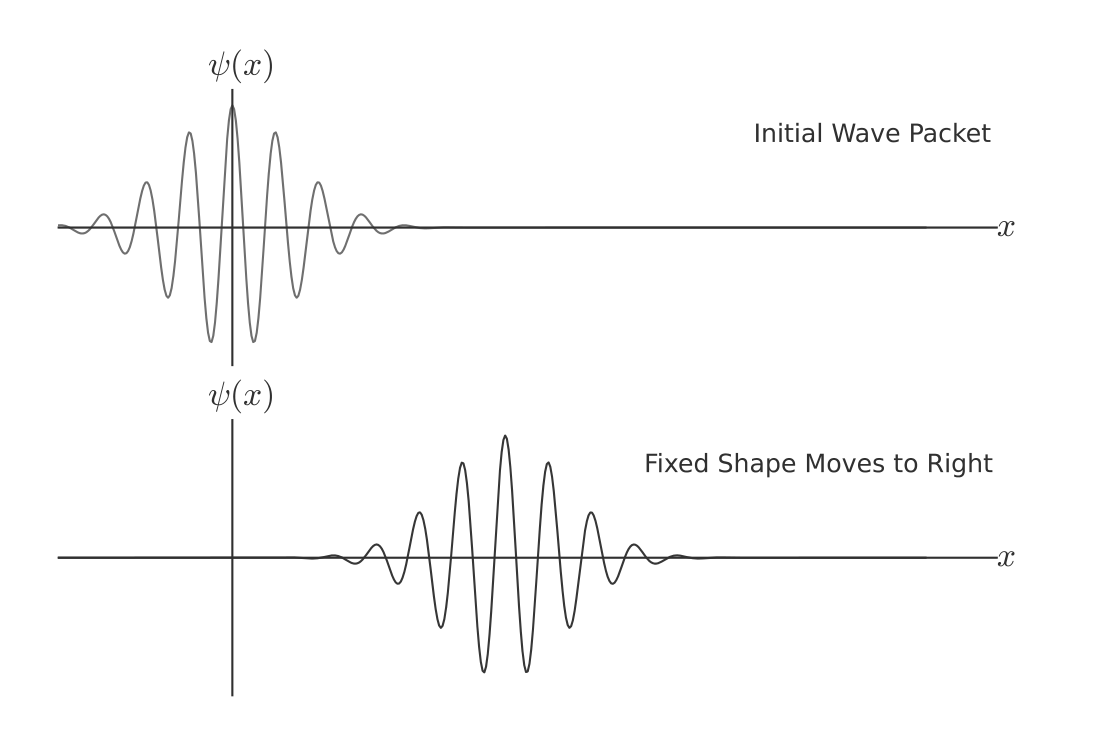

A simplest Hamiltonian is $H = cP$, where c is a fixed number. If we apply above equation here, we get, $i\hbar \frac{\partial \psi(x, t)}{\partial t} = -c i \hbar \frac{\partial \psi(x, t)}{\partial x}$. Which leads to $\frac{\partial \psi(x, t)}{\partial t} = -c \frac{\partial \psi(x, t)}{\partial x}$. Any function $\psi(x - ct)$ solves this equation.

At T = 0, we have some function $\psi(x)$. Note that due to normalization contraints, this function has to go to zero towards the ends. The wave function might look something like this.

At later time, T = t, $\psi(x-ct)$ has the same shape as $\psi(x)$ but shifted to the right by ct. It is equivalent to say that the wave has translated to the right in space. This translation happens at uniform velocity. If we let c to be the speed of the light, this Hamiltonian almost describes the 1d neutrinos, except that our H only describes particle moving to the right.

Since the wave function moves rigidly to the right, the expected value also moves to the right at the same velocity. In classical mechanics if let $H = cP$, the Hamiltonian equations give us following equations.

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial H}{\partial p} &= \dot{x} = c \\ \frac{\partial H}{\partial x} &= -\dot{p} = 0 \\ \end{align*} $$

Thus classically, the momentum is conserved, and the particle moves with the constant velocity c.

Non relativistic Particles#

Particles that have some mass, can not travel at the speed of light. Classically, a free particle (i.e., zero potential energy) has the Hamiltonian $\frac{p^2}{2m}$.

Inspired from it, we can imagine that QM has hamiltonian $\frac{P^2}{2m}$. When we put definition of P into time-dependent Schrodinger’s equation, we get $\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} = \frac{i \hbar}{2m} \frac{\partial^2 \psi}{\partial x^2}$.

Susskind’s book says that waves with different wavelength travel with different velocities, so this wave changes the shape with time. I don’t understand this chain of thoughts.

There are two explanations I found on the Internet. Here.

- One explanation is connection with heat equation. The Schrodinger’s equation above, is partial differential equation in the form of heat equation. Heat equation says that waves where the curvature is high, dissipates faster.

- Another explanation is that initially we have some uncertainity in the position, and some uncertainity in the momentum (i.e., velocity). Smaller the uncertainity in position, larger the uncertainity in velocity. So overtime, this uncertainity in position increases(due to initial uncertainty in velocity), and the wavefunction spreads.

Time evolution of the non-relativistic particle.#

We follow the recipe outlined earlier.

- Find the H somehow. Done: $H = \frac{P^2}{2m}$.

- Find the eigenvalues for this H. This is easy. Eigenvectors $\frac{P^2}{2m}$ are same as eigenvectors of P. Just the eigenvalues change to $\frac{p^2}{2m}$. $E(p) = e^{\frac{ipx}{\hbar}}$.

- Prepare the state in the initial state $\Psi$.

- Use the continuous counterpart of $\Psi(t) = \sum_j \ket{E_j}\braket{E_j|\Psi(0)} e^{-\frac{i}{\hbar}E_j t}$ to find the state at later time. So,

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x, t) &= \int \text{exp}\left(\frac{i p x}{\hbar}\right) \psi(p) \text{exp}\left({-\frac{i p^2 t}{\hbar 2 m}}\right) dp \\ &= \int \psi(p) \text{exp}\left({\frac{i\left(px - \frac{p^2 t}{2 m}\right)}{\hbar}}\right) dp \end{align*} $$

Of course, I have abused the notation. A lot.

If we compare the last equation to fourier formula, we get $\psi(p, t) = \psi(p) \text{exp}\left({\frac{-i\frac{p^2}{2 m}}{\hbar}}\right)$.

Note: This formula might be wrong. Book has it $\psi(p, t) = \psi(p) \text{exp}\left({\frac{i\left(px - \frac{p^2}{2 m}\right)}{\hbar}}\right) dp$. But, it didn’t mention how it got it. Things are becoming crazy. I might have missed something. Or it is just a typo in the book.

Anyway, both the formulas suggest that P(p, t) is equivalent to P(p, 0). This is because momentum is conserved when there is no external force.

Expected Change in Position#

Since the wave function changes with time, the expected value of x, i.e., $\braket{\Psi|X|\Psi}$ also changes with time. There are two ways to compute this quantity. One is bruteforce, and one is to use commutators.

Using commutators is easy. We use the relationship proved here. $\frac{d \braket{X}}{dt} = \frac{-i}{\hbar 2 m} \braket{[P^2, X]} = \frac{-i}{\hbar 2 m} \braket{P[P, X] + [P, X]P} = \frac{-i}{\hbar 2 m} \braket{-2 i \hbar P} = \frac{\braket{P}}{m}$.

This is similar to classical v = p/m.

I will probably not do the bruteforce. But the in the 10th Lecture Prof. Susskind does that.

Non relativistic particle, with some forces on it#

In CM, we replace all the forces acting on the particle by a potential function. That is $F(x) = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial x}$. The Hamiltonian in CM is K + V. So, our quantum Hamiltonian should have V operator. The V operator is defined on wave functions, and is, $V\psi(x) = V(x)\psi(x)$. Just multiply by V(x).

Classically, the momentum does not depend upon forces on the particle. It is just v/m. Thus our update in the Hamiltonian should not change $\frac{d \braket{X}}{dt}$ that was derived earlier. Indeed, the new commutator will be just $[P^2 + V, X] = [P^2, X] + [V, X]$. Remember, commutators are linear, and so are expectations. Also, V and X commute with each other. That is easy to see when you use the definitions of V and X. So $[V, X] = 0$. Hence, $\frac{d \braket{X}}{dt} = \frac{\braket{P}}{m}$ still holds.

Classically, $\frac{dp}{dt} = F = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial x}$. Let’s see what happens in the quantum realm.

$\frac{d \braket{P}}{dt} = \frac{i}{\hbar} \braket{[P^2+V, P]} = \frac{i}{\hbar} \braket{[V, P]}$.

It is easy exercise to show that $[V, P] = i \hbar \frac{\partial V}{\partial x}$.

And hence, $\frac{d \braket{P}}{dt} = - \braket{ \frac{\partial V}{\partial x}}$.

It is important to note that $\frac{d \braket{P}}{dt} \ne - \frac{\partial \braket V}{\partial x}$.

For example, take a bimodal distribution, where one peak is at -5 and another one at 5. Let $F(x) = x^2$. Since, the expected value of x is 0, $F(\braket{x}) = F(0) = 0$. On the other hand, $\braket{F(x)}$ is not zero.

When the wave function is concentrated over a fairly narrow range, only then $\braket{F(x)} = F(\braket{x})$.

Following are statements from the book. I am unable to prove it or find the proofs in the book. So pasting them verbatimly.

If V varies rapidly across the wave packet, the classical approximation will break down. In fact, in that situation a nice, narrow wave packet will get broken up into a badly scattered wave that has no resemblance to the original wave packet.

Path Integrals#

In classical mechanics, given that particle is at x1 at time t1, and is at x2 given t2, the path the particle takes is the one that minimizes the action.

Similar notion is for quantum mechanics, called path integrals. Here, we say that given that particle is at x1 at time t1, what is the probability (or amplitude) at x2, t2.

The initial state is $\ket{\Psi(t_1)} = \ket{x_1}$. The time evolution gives us $\ket{\Psi(t_2)} = e^{-i H (t_2-t_1)} \ket{x_1}$. So the amplitude at position x2 is given by $\braket{x_2|\Psi(t_2)} = \braket{x_2|e^{-i H (t_2-t_1)} | x_1}$. We replace t2-t1 by t.

$\braket{x_2|\Psi(t_2)} = \braket{x_2|e^{-i H t} | x_1}$. Using the decomposition $e^{-i H t} = e^{-i H \frac{t}{2}}e^{-i H \frac{t}{2}}$, and $I = \int dx \ket{x}\bra{x}$, we get, $\braket{x_2|\Psi(t_2)} = \int {dx \braket{x_2|e^{-i H \frac{t}{2}} | x} \braket{x|e^{-i H \frac{t}{2}} | x_2}}$.

But, there is nothing special about t/2. We can divide the path into N segments, each with length $\epsilon$. If we denote $U = e^{-i\epsilon H}$, $\braket{x_2|\Psi(t_2)} = \braket{x_2|U^N|x_1}$.

What Feynman discovered was that for each path, there is an action A. And that $\braket{x_2|\Psi(t_2)} = \int_{paths} e^{iA/\hbar}$.

Harmonic Oscillators#

Harmonic oscillators is a mathematical framework. Many natural phenomenon have oscillation property. Ideallized spring for example follows Hook’s law. That is, force is proportional to the displacement. $F = -kx$. Thus, $V = kx^2/2$.

Many energy functions approximate quadratic function, around minima.

Examples,

- Waves: Sound waves and water waves. At particular position, water molecules oscillates.

- Electromagnetic waves: Same mathematics as normal waves.

- Electric current in a low resistance often oscillates with a charateristic frequency.

All these, have the same mathematics.

Classical Spring#

$ L = K - V = \frac{m \dot{y}^2}{2} - \frac{k y^2}{2}$. If we let $x = \sqrt{m}y$, the lagrangian becomes, $L = \frac{ \dot{x}^2}{2} - \frac{\omega^2 x^2}{2}$, where $ \omega = \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}$. Omega happens to be the frequency of the oscillation.

We changed the variable to convert into the common form. In the common form, every osillator just changes the omega.

For one dimensional motion, Lagrange’s equation is $\frac{\partial L}{\partial x} = \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot x}$. Solving this gives us $-\omega^2 x = \ddot{x}$. The minus sign is there to tell us that acceleration is opposite to the displacement. This equation is exactly same as $F = ma$. The general solution of this is $x = Acos(\omega t) + Bsin(\omega t)$. This confirms that, omega is the frequency.

“Quantum Spring”#

Many molecules consist of two atoms - for example, a heavy atom and a light one. There are forces holding the molecule in equilibrium with the atoms separated by a certain distance. When the light atom is displaced, it will be attracted back to the equilibrium location.

States in 1-dimensional motion, for small particles, is given by state vectors $\psi(x)$. This $\psi$ has to follow certain conditions, like normality, and waning to zero at infinities.

The canonical momentum conjugate to x is defined as $p = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{x}} = \dot{x}$. Thus, the classical Hamiltonian is given by $H = p\dot{x} - \mathcal{L}$. One can use the definition of Lagrangian to figure out the Hamiltonian. It turns out to be $H = \frac{\dot{x}^2}{2} + \frac{\omega^2 x^2}{2}$. But, the velocity does not have quantum operator, so we replace velocity by canonical conjugate momentum. $H = \frac{p^2}{2} + \frac{\omega^2 x^2}{2}$.

The Quantum counterpart is, $H = \frac{P^2}{2} + \frac{\omega^2 X^2}{2}$.

The algebra will tell us that, $H \ket{\psi(x)} = -\frac{\hbar^2}{2} \frac{\partial^2 \psi(x)}{\partial x^2} + \frac{1}{2} \omega^2 x^2 \psi(x)$.

Time dependent Shrodinger’s Equation#

$$ \begin{align*} i \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} &= \frac{1}{\hbar} H \psi \\ &= -\frac{\hbar}{2} \frac{\partial^2 \psi}{\partial x^2} + \frac{1}{2\hbar} \omega^2 x^2 \psi \\ \end{align*} $$

One can use computational methods to solve these equations. But, another way to solve is to use time-independent schrodinger’s equations.

Time independent Schrodinger’s equations#

We can find eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the H, and follow the recipe outlined earlier.

$$ \begin{align*} H \ket{\Psi_E} &= E \ket{\Psi_E} \\ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2} \frac{\partial^2 \psi_E(x)}{\partial x^2} + \frac{1}{2} \omega^2 x^2 \psi_E(x) &= \psi_E(x)\\ \end{align*} $$

We want to find E, and associated $\Psi_E$ that solve this equation. But, as it turns out, most of the solutions for E, including all the complenumbers, have associated $\Psi_E$ which blows up as x approaches one or both infinities. So, we want the E, and associated $\Psi_E$ where $\Psi_E$ is normalizable.

Smallest eigenvalue#

Classical oscillator does not have negative energy. The reason for it is that it has square terms $x^2$ and $p^2$ in it. But, zero is the minimum energy, arrived when $x = p = 0$.

Quantum oscillator, has $X^2$ and $P^2$, both of which has non-negative eigenvalues. So the minimum energy has to be non-negative. (Because we have $P^2/2 + \omega^2/2 X^2$. A non-negative sum of positive semi-definite matrices is also positive semi-definite. I assume that argument would hold true for complex operators as well.) But, in QM, as per heisenberg’s uncertainy principle, we can’t set $X = P = 0$. The state associated with the lowest positive eigenvalue is known as ground state, and is denoted as $\Psi_0$.

There is a theorem which helps us find the eigenfunction associated with the smallest eigenvalue.

The ground-state wave function for any potential has no zeros and it’s the only energy eigenstate that has no nodes.

One such function is $\psi(x) = e^{\frac{-\omega}{2\hbar}x^2}$. This function, is concentrated around x = 0, as would be required for minimum valued eigenfunction.

When we put this function in the time independent schrodinger’s equation, we will get $\frac{\hbar}{2} \omega e^{\frac{-\omega}{2\hbar}x^2} = E e^{\frac{-\omega}{2\hbar}x^2}$. The only solution is to set $E = \frac{\omega \hbar}{2}$.

Thus we have groundstate $\psi_0(x) = e^{\frac{-\omega}{2\hbar}x^2}$ and groundstate energy $E_0 = \frac{\omega \hbar}{2}$.

Other way to look#

So far we have looked at functions. Another way to look is abstract method. Our operator is $H = \frac{1}{2} (P^2 + \omega^2 X^2)$.

It is easy to write $H = \frac{1}{2}(P + i\omega X)(P - i\omega X) + \frac{\omega \hbar}{2}$. (Hint: $[X, P] = i\hbar$).

Due to the history, we define $a^{-} = \frac{i}{\sqrt{2\omega \hbar}} (P - i \omega X)$ and $a^{+} = \frac{-i}{\sqrt{2\omega \hbar}} (P + i \omega X)$.

Properties of $a^+, a^-$.

- $(a^-)^\dagger = a^+$

- $[a^-, a^+] = 1$

After these definitions, $H = \omega \hbar (a^+ a^- + 1/2)$. If we define $N = a^+ a^-$, $H = \omega \hbar (N + 1/2)$.

- $[a^-, N] = a^-$

- $[a^+, N] = - a^+$.

Why are these important?#

Say you had and eigenpair for N, $N \ket{n} = n \ket{n}$, what happens if I apply N to $a^+ \ket{n}$? $$ \begin{align*} N (a^+\ket{n}) &= (a^+ N - (a^+ N - N^a+)) \ket{n} \\ &= n a^+ \ket{n} - [a^+, N]\ket{n} \\ &= n a^+ \ket{n} + a^+ \ket{n} \\ &= (n+1) a^+ \ket{n} \end{align*} $$

Thus, $a^+ \ket{n}$ is the eigenvector with next eigenvalue. i.e., $(a^+ \ket{n}) = \ket{n+1}$.

Similarly, $N a^- \ket{n} = (n-1) a^- \ket{n}$, and $a^-\ket{n} = \ket{n-1}$.

Because of these, $a^+$ is known as raising operator, and $a^-$ is known as lowering operator.

By the way, since $H = \omega \hbar (N + 1/2)$, lowering can’t continue indefinitely, otherwise H might end up with negative eigenvalues. Thus, for the smallest eigenvector, call it $\ket{0}$, $a^- \ket{0} = 0$. This vector, solves the time-independent schrodinger’s equation for $E_0 = \omega \hbar /2$.

$E_n = \omega \hbar (1/2, 3/2, 5/2, \dots)$.

But, what is the ground state?#

We can find the ground state by using the lowering operator on the $a^-$. $ \frac{i}{\sqrt{2 \pi \hbar}} (P - i \omega \hbar X) \psi_0{x} = 0$.

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{i}{\sqrt{2 \pi \hbar}} (P - i \omega \hbar X) \psi_0{(x)} &= 0 \\ (P - i \omega \hbar X) \psi_0{(x)} &= 0 \\ -i \hbar \frac{\partial \psi_0{(x)}}{\partial x} - i \omega x \psi_0{(x)} &= 0 \\ \frac{\partial \psi_0{(x)}}{\partial x} = -\frac{\omega x}{\hbar} \psi_0{(x)} \end{align*} $$

This solution has equation $\psi_0{(x)} = e^{-\frac{\omega}{2 \hbar} x^2}$.

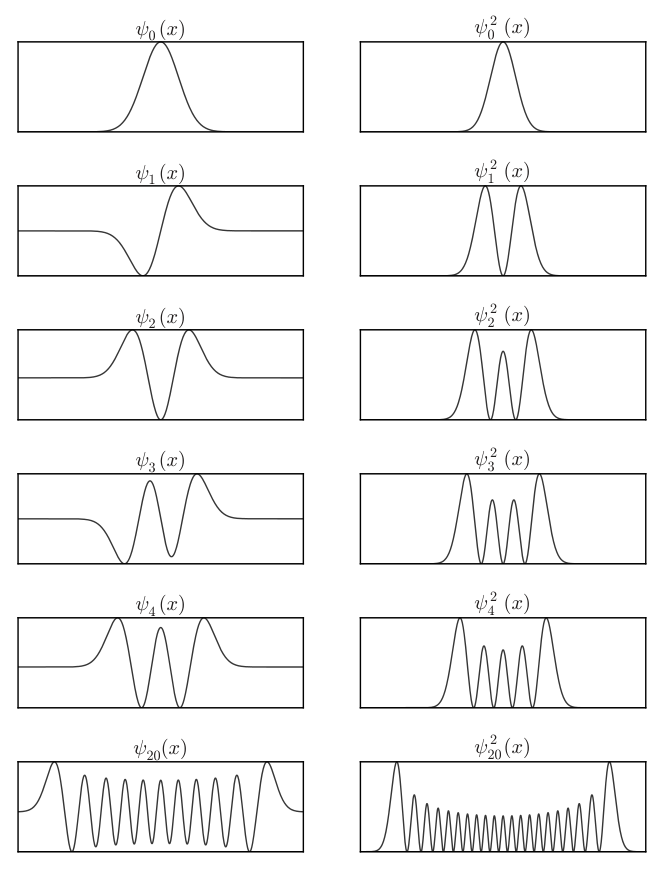

The next eigenvectors can be found by using $a^+$ operator on the ground state. Not doing the algebra here, but the solutions for the next two states are below.

$$ \begin{align*} \psi_1(x) &= \frac{2 \omega x}{\sqrt{2 \pi \hbar}} e^{-\frac{\omega}{2 \hbar} x^2} \\ \psi_2(x) &= \frac{\omega}{\pi \hbar} (-\hbar + 2 \omega x^2) e^{-\frac{\omega}{2 \hbar} x^2} \\ \end{align*} $$

It is easy to notice that for each step higher in the eigenstate, we have higher degree polynomial multiplied by the ground state. As the degree of the polynomial increases, the zeros of the statefunction, and nodes of the amplitudes increase. Thus, higher energy wave functions have higher frequency, implying higher momentum. Also, since the exponential goes to zero faster than the polynomial, the wave function are “good”, i.e., they go to zero towards the infinities.

Although, they approch zero towards infinities, they are not quite zero. That means there is positive probability of finding particles outside of the “potential bowl”. This phenomenon is known as quantum tunneling.